Associated Locations:

- Free Imperial City of Frankfurt, Holy Roman Empire – Birthplace

Associated Dates:

- August 28, 1749 – Born

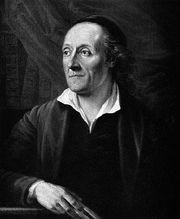

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is one of the eminent spirits who appeared to President Wilford Woodruff in the St. George Temple on August 21, 1877. This interesting story is detailed in the Eminent Spirits Appear to Wilford Woodruff wiki.

“To the enduring names of Shakespeare, Homer, and Dante, the student of history and literature must add the immortal name of the German-born poet, Goethe. Goethe’s mind and soul were so elevated and sublime that few have been his equal. His reputation was established almost overnight, and he was well-known all over Europe. His talent and perceptions were revered and sought by all, from Napoleon to Sir Walter Scott.” 1

“If man was of divine origin, so was also language… These two things, like soul and body, I could never separate… God had played the schoolmaster to the fist men.”

-Goethe

Life Sketch from The Other Eminent Men of Wilford Woodruff

Copyright © Taken from the book: The Other Eminent Men of Wilford Woodruff. Special thanks to Vicki Jo Anderson. Please do not copy.

Father of German Literature 1749-1832

From the time he was a young man, Goethe saw not only the weight and fetters of daily life, but he also saw events in daily life as part of a much larger and more important picture. “Every situation–nay, every moment is of infinite worth,” he said, “for it is the representative of a whole eternity.”

Like Shakepeare and others, Goethe rooted himself in the unchanging principles of human nature. He was convinced that no matter how tempted and tried man may be, good will always triumph over evil. “I believe in God,” Goethe told Eckermann, a close associate and secretary, “in Nature, and in the triumph of good over evil.” Upon completing his most enduring work, Faust (which took fifty years to complete), Goethe enlarged upon this belief: “In Faust himself there is an activity which becomes constantly higher and purer to the end, and from above there is eternal love coming to his aid. This harmonizes perfectly with our religious view, according to which we cannot obtain heavenly bliss through our own strength alone, but with the assistance of divine grace.

Most histories describe Goethe as a philosopher as well as a writer. However Goethe disdained philosophy of his day. Goethe agreed with the premise, “There is a point of view beyond the sphere of philosophy, namely, that of common sense…. I have always kept myself free from philosophy.” Goethe felt that the Germans had wasted their time and energy in trying to find the solutions to philosophical problems, while the English with their great practicality were winning the world.

As a young student he debated the issue of philosophy with a fellow boarder. His opponent had studies at the University of Jena and contended that religion and poetry found their basis in philosophy.” Young Goethe stubbornly opposed this view. As a result of this encounter Goethe began an intense study of the history of philosophy. Among the ancients, he discovered a more pure philosophy that that of his day because, as he noted, it was there that he found poetry, religion, and philosophy all combined into one. In his studies of the ancients he always included the first five books of the Old Testament. Socrates he esteemed as well, proclaiming him an “excellent wise man.”

Belief in God

Historians record that Goethe denied being a Christian, giving as evidence Goethe’s encounter with the noted Reverend Lavater. Lavater, who was as extreme as he was narrow in his view, challenged Goethe to declare whether or not he was a Christian. Not, Goethe replied, if he had to use Lavater’s definition. According to Christian belief, man was born evil and Goethe could not agree with this. To the end of his life he felt that man was essentially good and trying to overcome the evil in the world around him.

Goethe always worked to help others maintain the good in themselves and felt great disdain for those who criticized others. He felt that doing so only caused personal destruction and brought great pain to all involved. “For the point is,” he said, “not to pull down, but to build up, and in this humanity finds pure joy.”

Goethe felt that man had a special relationship with deity, even when he was sometimes left tp his own resources for his growth:

For a time we may grow up under the protection of parents and relatives; we may lean for awhile upon our brothers and sisters and friends, be supported by acquaintances and made happy by those we love; but, in the end man is always driven back upon himself; and it seems as if Divinity had taken a position toward men so as not always to respond to their reverence, trust and love, at least, not in the precise moment of need. Early enough, and by many a hard lesson, had I learned that in the most urgent crises, the calls to us is, “Physician, heal thyself”; and how frequently had had I been compelled to sigh out in pain, “I tread the wine-press alone!…” While then, I reflected upon this natural gift.

Goethe often reflected upon those divine gifts given to man in varying degrees. Those he most often referred to as possessors of divine gifts were Friedrich Schiller, Lord Byron, Robert Burns, Walter Scott, Napoleon, and Shakespeare. Referring to Hamlet, Goethe described it “as a pure gift from above.” Goethe further felt that “every extraordinary man has a certain mission which he is called upon to accomplish.” He felt that he had received gifts from above. When the people sought to tear him down, he saw it as a foolish attempt to amend the purpose God had laid out for him.

Although Goethe chose not to be aligned with the Christian sects of his day, religion was always important to him. Goethe spent fifty years studying church history, often in its original language. The Old Testament was an integral part of his way of thinking and he often stated that truly great genius and art was never achieved without being integrally connected to religion. In any art he, he maintained, little can be achieved if it is divorced form serious and noble thought. Goethe had definite ideas about how this union could be brought about in literature. “If any man wish to write a clear style, let him be fist clear in his thoughts; and if any would write in a noble style, let him first possess a noble soul.”

“What would be the use of poets,” Goethe further noted, “if they only repeated the record of the historian? The poet must go further and give us, if possible, something higher and better.” And “Here is the grand point and out present poets should do like the ancients. They should not be always asking whether a subject has been used before, and look to south and north for unheard-of-adventures, which are often barbarous enough, and merely make an impression as incidents. But to make something of a simple subject by a masterly treatment requires intellect and great talent, and these we do not find.” He detested those poets who wrote only of the woes and miseries of the life ans spoke only of the joys of an afterlife. “This is the real abuse of poetry, which was give to us to hide the little discords of life, and to make man contented with the world and his condition.” He cautioned readers of poetry and viewers of art not to dissect each phrase or each brush stroke, but to look upon the work as a whole, for therein lay its beauty.

Goethe’s understanding of the ancients came through diligent study. Through them he sought for the truly enduring elements in life. Of the ancients he wrote: “People always talk of the study of the ancients; but what does that mean, except that it says, turn your attention to the real world, and try to express it, for that is what the ancients did when they were alive.”

Encouraging all to study the classics, Goethe said, “The antique is classic, not because it is strong, fresh, joyous, and healthy.” He added further to his definition of a classic when he said, “The point is for a work to be thoroughly good and then it is thoroughly sure to be classical.”

Goethe’s own works fulfill his definition in every particular. It would be a shall critic who limited Goethe in his expansive scope. Those of his contemporaries were often too close to see how great he truly was. Our distance by now should give us a view of him in his true proportions.

Early Life

Johann Wolfgang Goethe was born in Frankfort, 28 August 1749. His father, Johann Kaspar von Goethe, a lawyer who inherited a family fortune, was a stern and self-righteous man, but thoroughly honest. Combined with these attributes was a sound knowledge and a deep appreciation for art and literature.

Conscious of his abilities and distrustful of the teachers of the day, Johann Kaspar undertook to instruct his two children, Johann Wolfgang and his sister, Cornelia, at home, using tutors only when absolutely necessary. Goethe recalls that because of his prodigious memory he learned easily without having to really apply himself. Grammar was distasteful to him, be he learned Italian easily just by listening to his sister’s tutor. The book Robinson Crusoe led him to dream of adventure. By the age of ten his Latin was flawless.

In intelligence and dignity, Goethe’s mother, Catherine Textor, was like her husband. However, in temperament she was merry, genial and whole hearted. She was one of those rare women who make the world a happier place just by their presence in it. Her good humor was contagious, and she saw only the sunny side of life.

Much of Goethe’s personality came from his mother and much of his natural ability for deep insight from his maternal grandfather, who was the chief magistrate of Frankfurt. Goethe’s intellectual foundation was firmly laid by his father who devoted his entire day to his children’s education. Because their rigorous education often lasted from morning until evening, the children were only too glad to enjoy and evening visit with their mother, who was noted for her story telling. Goethe would likewise entertain his friends with his own stories.

The elder Goethe, having spent some time in Italy, took great pains to have good at in the home. Goethe said that cleanliness and order prevailed throughout and his father maintained an excellent collection of books.

Goethe adored his grandparents. From his paternal grandmother, who lived with them until her death, the children received a puppet theater. For many years Goethe and Cornelia wrote and produced puppet shows. Form these simple beginnings came one of the world’s greatest dramatists. The adoration Goethe felt for his maternal grandfather is evidence in the following:

The reverence we entertained for this venerable old man was raised to the highest degree by a conviction that he possessed the gift of prophecy, especially in matters that pertained to himself and his destiny and minutely, except to my grandmother; yet we were all aware that he was informed of what was going to happen by significant dreams.

Though Goethe was very circumspect about his own personal experiences, there is enough evidence in his multitude of writings to see that he was heir to his grandfather’s gift of prophecy. He tells of his parting, he thought for the last time, from his girlfriend, Fredricka, who lived in the country: “I rode along,” he recalled, “…and here one of the most singular forebodings took possession of me. I saw, now with the eyes of the body, but with those of the mind, my own figure coming toward me, on horseback, and on the same road, attired in a dress which I had never worn.” Goethe shook himself free of the strange vision. Strangely, eight years later he found himself on the very same road, dressed as he had seen himself.

Goethe’s father rigorously guarded his children’s curriculum. However, Goethe and Cornelia were able to smuggle a copy of Klopstock’s “Messiah.” The elder Goethe had forbidden Klopstock’s work in their home not because of the content, but because it was not in the traditional meter. The two children, memorized and acted out the entire poem in secret. One day while their father was being shaved, Cornelia secretly acted out part of the “Messiah.” When she came to an especially dramatic part, she shouted out, causing her father to spill his wash basin, and he immediately confiscated the smuggled poem.

About the time of Goethe’s seventh birthday, Europe was shaken by the outbreak of the Seven Year War. Goethe’s maternal grandfather sided with Empress Theresa and the Austrians while his father was an enthusiastic follower of Frederick the Great. This difference of opinion led to serious family disagreements.

It was an especially bleak day for his father when the French, who were allies of the Austrians, occupied Frankfort. To his father’s great horror, the head French officer, Thorane, chose the Goethe home for his headquarters. Thorane was a circumspect gentleman, highly cultured and educated. He and young Goethe soon became friends, and Goethe rapidly became fluent in French. Because of Thorane, Goethe had free admittance to all the French plays, an activity which opened many avenues in the young boy’s mind. Thorane also brought in his own art and artist. Goethe was so taken by French culture that for a number of years his thinking showed a strong French influence. This influence persisted until he fell under the spell of Shakespeare, whom he felt revealed a higher and freer view to the world with intellectual enjoyments as true as they were poetical. He described “the influence this extraordinary mind” upon him. “But we cannot talk of Shakespeare; everything is inadequate.”

By the time Goethe was twelve years old he had a good knowledge of seven languages–Latin, Italian, French, English, Greek, Hebrew, and of course, German. For one of his father’s assignments he chose to form a dialogue of various correspondents from different parts of the world each letter was written in the correspondent’s native tongue.

In his fifteenth year, he had his first romance. This became the first long line of girls ans women who had a deep, almost mystical affect on him. He held women in highest esteem, adoring their divine origin. Each one he fell in love with appears as a character in one of his great plays. “My idea of women is not abstracted from the phenomena of actual life,” he told Eckerman, “but has been born with me, or arisen with me, God knows how.” No poet was perhaps more susceptible for feminine influence that Goethe, and except for Shakespeare he did more for the position of women that had been done in the preceding four hundred years.

When Goethe turned sixteen, he bade his family farewell and set out for Leipsig, where he was to study law. Although the study of law was not to his liking, Goethe persisted. To complete his studies he wrote a dissertation, which filled two volumes. The elder Goethe was so pleased with his son’s accomplishments that he tried to get the two volumes published, but not one publisher would publish it. Ironically, Goethe’s father felt that he had failed, that all his efforts in educating this child had come to naught. But time and patience would prove that his efforts had contributed to the making of the greatest literary genius Germany had ever seen.

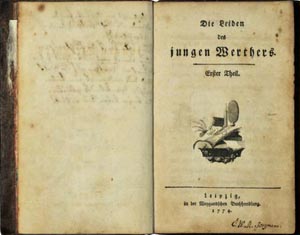

Works

Goethe’s first work of note was the historical play Gotez von Berlichingen. Because of this play the poetic value of the Middle Ages was rediscovered. As Goethe wrote more, he gave rise to the literary movement called Sturm und Drang (or “Storm and Stress”). This movement unlike the bloody French Revolution, was a revolution through literature. The school of Enlightenment had emphasised the tights of reason. Sturm und Drang clamored for the rights of the heart to be added to reason.

Goethe’s work’s attracted the attention the great Duke of Weimar, who sought out men such as Goethe, Herder, Wieland, Schiller, and others to be part of his little kingdom. Here the great minds and souls of German talent were allowed to flourish.

Goethe served the duke faithfully, watching over the theater at Weimer with particular care. In addition to his writings, he also worked to advance the University of Jena. Of education, he said: “They teach in a academies far too many things, and far too much that is useless.” Basis to all education he felt was to have a soul that loves truth and receives it wherever it finds it.

Goethe was lived to the age of eighty-three, thus becoming the sage of all of Europe. He was preceded in death by his devoted wife Christiane and their only son. Goethe had no fear of death, though he felt deeply about those he lost. At the age of seventy-five while reflecting upon the possibility of dying he stated:

One must, of course, think sometimes of death. But this though never gives me the least uneasiness, for I am fully convinced that our spirit is a being of nature quite indestructible, and that its activity continues from eternity to eternity. It is like the sun, which seems to set only to our earthly eyes, but which, in reality, never sets, but shines on unceasingly.

Schiller, Goethe’s friend and fellow writer, wrote in tribute to the great master: ‘He stood beside me like my youth, making actual existence a dream to me, weaving golden vapors of the dawn about the common realities of life. In the fire of his loving soul, even the plain, every-day objects of life became, to my astonishment, exalted.”

Although Goethe’s sun upon his life has set, his work has radiated for nearly two centuries. In his last moments he was heard to utter these words: “More light!”

Copyright © Taken from the book: The Other Eminent Men of Wilford Woodruff. Special thanks to Vicki Jo Anderson. Please do not copy.

2