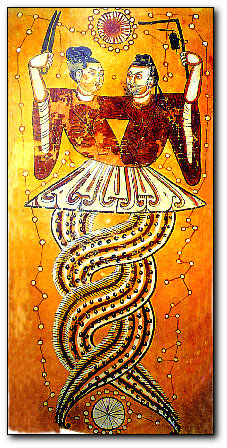

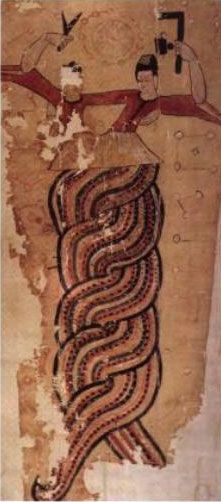

Fu Xi and Nuwa are considered, in Chinese history, as the founders and first rulers of China. They are depicted on tapestries, stone and veils found in Chinese tombs.

Fu Xi is credited with bringing moral standards to China.

In the beginning there was as yet no moral or social order. Men knew their mothers only, not their fathers. When hungry, they searched for food; when satisfied, they threw away the remnants. They devoured their food hide and hair, drank the blood, and clad themselves in skins and rushes. Then came Fu Xi and looked upward and contemplated the images in the heavens, and looked downward and contemplated the occurrences on earth. He united man and wife, regulated the five stages of change, and laid down the laws of humanity. He devised the eight trigrams, in order to gain mastery over the world. — Ban Gu, Baihu tongyi

Depicted Symbols

Included on the depictions of Fu Xi and Nuwa are symbols of particular interest to Latter-day Saints.

Hugh Nibley wrote in Temple and Cosmos

Most challenging are the veils from Taoist-Buddhist tombs at Astana, in Central Asia, originally Nestorian (Christian) country, discovered by Sir Aurel Stein in 1925…

We see the king and queen embracing at their wedding, the king holding the square on high, the queen a compass. As it is explained, the instruments are taking the measurements of the universe, at the founding of a new world and a new age. Above the couple’s head is the sun surrounded by twelve disks, meaning the circle of the year or the navel of the universe. Among the stars depicted, Stein and his assistant identified the Big Dipper alone as clearly discernable. As noted above, the garment draped over the coffin and the veil hung on the wall had the same marks; they were placed on the garment as reminders of personal commitment, while on the veil they represent man’s place in the cosmos.

. . .

In the underground tomb of Fan Yen-Shih, d. A.D. 689, two painted silk veils show the First Ancestors of the Chinese, their entwined serpect bodies rotating around the invisible vertical axis mundi. Fu Hsi holds the set-square and plumb bob … as he rules the four-cornered earth, while his sister-wife Nü-wa holds the compass pointing up, as she rules the circling heavens. The phrase kuci chü is used by modern Chinese to signify “the way things should be, the moral standard”; it literally means the compass and the square. 1

Another description is found in The Magic Square: Cities in China by Alfred Schinz:

It appears from these legends that civilization, i.e. ordered human life, begins with two personages, both portrayed as being semi-human and with mermaid tails. Nüwa and Fuxi, originally sister and brother, later became wife and husband after they had invented proper marriage procedures and family names to prevent marriages between people from the same family. Nüwa, in her own legend, had restored order between heaven and earth after a horrible catastrophe had caused heaven to tilt to the north so that it no longer covered all of the earth. This may refer to the first observation of the oblique elliptic and the angle of the pole star. Nüwa found it necessary to reestablish the four cardinal points, which she did, thereby creating the prerequisites for further observations. In the oldest pictures of her she carries a compass, the instrument related to heavenly observations. Her brother Fuxi became the first legendary emperor, which also implies the establishment of government, of law and order… On another, more practical level he is said to have invented axes for splitting wood, the carpenter’s square, ropes for hunting and fishing nets. It is worthy of special attention that the two words for compass and square, gui ju, used together denote -the rule, custom, usage- and -good behavior-, i.e., keeping order. Furthermore, it should be observed that the male-female system, the yang-yin philosophy, is expressed here in a complex manner, first as Fuxi and Nüwa, second as compass (male) and square (female), and third as Nüwa (female) with compass (male) and Fuxi (male) with square (female). The compass-square dichotomy is similar to the heaven-earth, yang-yin, relationship, which in this case means that man (Fuxi) establishes harmonious order between heaven and earth. This is also expressed in the Chinese character for king, wang, the upper and lower line indicating heaven and earth and the middle line man, all three connected by the vertical line. This represents the position and function of the ruler; it is he who establishes and keeps order by placing himself in a balanced and harmonious position between heaven and earth, so that yang and yin cooperate in a beneficial way.

[Caption] Fuxi and his sister Nüwa, he with the carpenter’s square and she with the pair of compasses. From the decoration incised in the wall of the Wu Lang tombs in Jiaxiang, Shandong, second century AD. The Chinese words for carpenter’s square, ju, and a pair of compasses, gui, together form the expression to establish order. This is what, according to their legends, Fuxi and Nüwa did. The carpenter’s square also stands for the square that is the symbol of the earth, while the pair of compasses represent the circle, the symbol of heaven. Fuxi, the male (yang), gives order to the earth (yin), and Nüwa, the female (yin), gives order to the heaven (yang).

2Other historians on the Fu Xi ans Nuwa symbols:

“In Chinese cosmogonic art during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.) two royal creator deities were depicted holding architectural implements that were used in the formation of heaven and earth—the compass and set-square (see Yves Bonnefoy, comp., Asian Mythologies [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993], 234–35). In a funerary context these beings served as “doorkeepers” or “guardians of boundaries” who “marked the division between inner and outer” spaces (cf. Gen. 3:24; Ex. 26:31). The depiction of these deities signified “transfer to another realm.” As early as the Warring States Period (475–221 B.C.E.) the Chinese compass and square “symbolized fixed standards and rules that impose order on unruly matter.” The Chinese deity who was shown holding the compass was associated with bringing “ordered space out of the chaos of the flood” (cf. the Hebrew concept) while the other, who held the square, was “’credited with the invention of kingship’” (Mark E. Lewis, The Flood Myths of Early China 3.

4“In traditional Chinese cosmology the earth was square and the heavens round and thus Fuxi holds a set square to draw the former, and Nüwa a pair of compasses to draw the circle of the earth.”

“This role of linking Heaven to Earth also figures in the depictions of Fu Xi and Nü Wa. First, in Han tombs their elongated, serpent bodies stretch from the bottom of the register to the top, and in later depictions this vertical ascent becomes even clearer. In Sichuan sarcophagi they play the iconographic role of the dragons on the Mawangdui banners who physically link the earthly realm to that of Heaven. This idea is reinforced through the regular inclusion of two other iconogrpahic traits. Fu Xi and Nü Wa are often depicted with the sun and moon, and they are shown holding a carpenters square (Fu Xi) and a drawing compass (Nü Wa). The former are metonyms for Heaven and the celestial equivalents of yin and yang. The latter suggests the linking of square Earth to the round Heaven. Most scholars agree that the role of the intertwined Fu Xi and Nü Wa was to depict the interaction of yin and yang that underlies cosmic order and thereby secure an auspicious environment for the denizen of the tomb.”

5“The Chinese picture illustrates in true archaic spirit (which means that only hints are given, and the spectator has to work out for himself the significance of the details) the surveying of the universe. The two characters surrounded by constellations are Fu Hsi and Nu Kua, i.e., the craftsman god and his paredra, who measure the “squareness of the earth” and the “roundness of heaven” with their implements, the square with the plumb bob hanging from it, and the compass. The intertwined serpent-like bodies of the deities indicate clearly enough, although in a peculiar “projection,” circular orbits intersecting each other at regular intervals.”

6“All “great instruments” were invented by the ancients to help lesser men “first rule the self and then rule others.” Although all are needed in construction, by no means do all these tools work in the same way. Level and line determine straight horizontal and vertical lines, while compass and square are needed to form perfect circles and corners. By analogy, each of the social institutions, including ritual, has its own function in building civilization, with each addressing a separate human need. It is characteristic of the sage-ruler that he always knows which tool to apply to the specific problem at hand.”

7

- Temple and Cosmos, Hugh Nibley, pg. 111-115

- Schinz, The Magic Square: Cities in Ancient China, 25-26, link

- Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006], 125–27

- Whitfield and Sims-williams, The Silk Road, 329, link

- Lewis, Writing and Authority in Early China, 204, link

- Giorgio De Santillana, Hertha Von Dechend, Hamlet’s Mill, 272, link

- Yan Hsiuing, Xiong Yang, Michael Nylan, The Elemental Changes: The Ancient Chinese Companion, 54, link.