William Makepeace Thackeray is one of the eminent spirits who appeared to President Wilford Woodruff in the St. George Temple on August 21, 1877. This interesting story is detailed in the Eminent Spirits Appear to Wilford Woodruff wiki.

Anthony Trollope, who was a friend of Thackeray, wrote of him; “Thackeray tells us that he was born to hunt out snobs.” Thackeray chose to dissect the middle and the upper classes–to turn the morality and mores inside and out. “You, dear reader,” wrote Thackeray, “have faults and petty vanities and I know them well for have I not those same frailties myself?” He is recognized as the first writer to have held a mirror up to society. His most valuable gift was his ability to observe. This gift was so keen that he was able to portray the hypocrisy of society and to strip off the layers of pretense.

“Indeed, it is something noble I think that God has a responding face for every one and sympathy for all.”

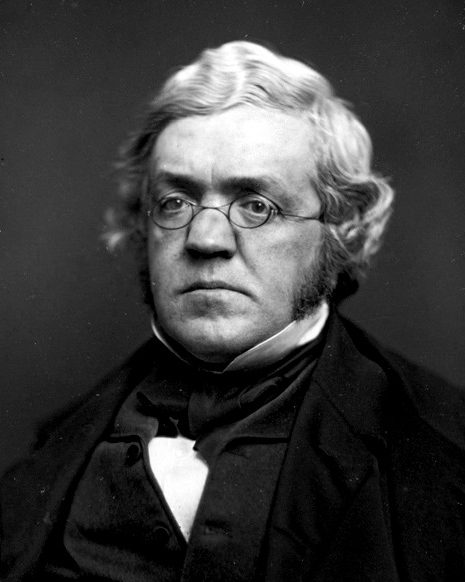

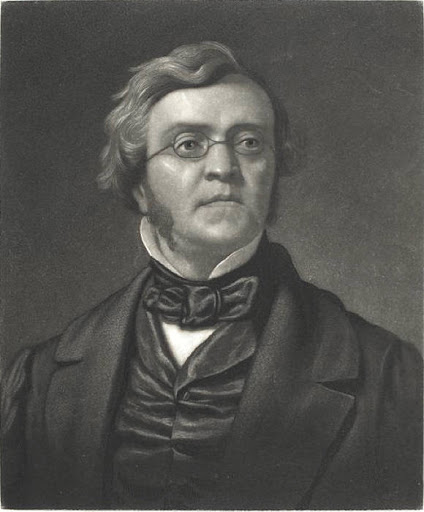

William Makepeace Thackeray

Life Sketch from The Other Eminent Men of Wilford Woodruff

Copyright © Taken from the book, The Other Eminent Men of Wilford Woodruff. Special thanks to Vicki Jo Anderson. Please do not copy.

English Humorist, Satirist, Novelist 1811-1863

The experiences of Thackeray’s life give him abundant material from which to draw for his writings. He traveled to France many times and to Ireland. He associated with people in all walks of life. He was born with status, but fell into poverty, and then rose to be one of the most famous men of the era. Although Thackeray was a product of the Victorian age, he felt and expressed the hypocrisy of the times. He held with the Victorian view of women, whom he saw as having great hearts, but little minds. He wrote that women were set apart as a higher order of moral beings. His early writings are full of parodies–the affectionate attack on accepted norms. A close friend wrote that the two secret keys of Thackeray’s great life were disappointment and religion. The first was his poison, and the second his antidote.

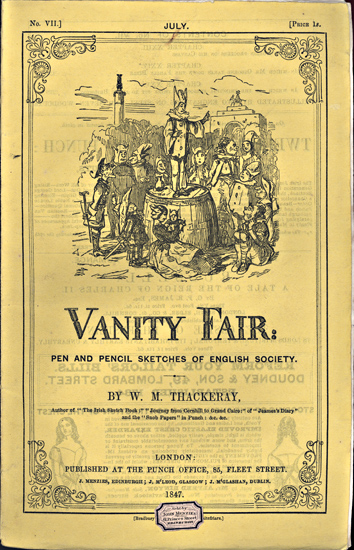

William Makepeace Thackeray, author of the social satire ‘’Vanity Fair’’, was one of the first writers to use literature as a means of social commentary. In his day, reactions to his writing were strong–both for good and ill. People could to read him without responding to him. Charlotte Bronte, who dedicated the second edition of her novel ‘’Jane Eyre’’ to him, spoke eloquently in his favor:

There is a man in our own days whose words are not framed to tickle delicate ears … who speaks truth as deep, with a power as prophet0like and as vital .. and as daring … I think if some of those amongst who he hurls the Greek fire of his sarcasm, and over whom he flashes … his denunciation, were to take his warnings in time, they or their seed might yet escape a fatal Ramoth-Gilead.

Why have I alluded to this man? I have alluded to him, Reader, because I think I see in him an intellect profounder and more unique than his contemporaries have yet recognized; because I regard him as the first social regenerator or the day–as the very master of that working corps who would restore to rectitude the warped system of things.

In his youth, upon a request by a newspaper, he wrote an article criticizing an eminent man who was becoming a baronet. Later, he wrote that he regretted having written the article, for the man was a great man. He readily admitted his mistakes as a youth and strove to never make the mistake again.

Family History

Thackeray’s family history is as interesting as any novel. The family’s ancient name was Thakwra, which was eventually changed to Thackeray. Thackeray’s grandfather transferred to India, where his son, Richmond, became on of the high officials of the East Indies. As a wise manager, Richmond was able to accumulate a modest fortune. Richmond was Thackeray’s father. His mother was Anne Becher.

Anne Becher had been sent to India by her stern grandmother. Anne had fallen in love with a young lieutenant she had met at a ball in Bath, England. He was of a good family, but as the second son, had no inheritance. Anne’s grandmother disapproved of the match and sought someone of higher status for he granddaughter. In spite of the grandmother’s protest the youths continued to see each other. When their meetings were discovered and stopped, they smuggled letters to each other. Then one day Grandmother came into Anne’s room and told her to prepare herself for a shock. She then told Anne that her young lieutenant had died.

Heartbroken Anne was sent to India to stay with relatives. English beauties were rare in India and dashing seventeen year-old Anne Becher was much sought after. She soon accepted Richmond Thackeray as her suitor and married him. The birth of Anne’s first child was extremely difficult and almost took Anne’s life. She was unable to have any more children after this birth. Her only child was a boy, William Makepeace.

Because of her husband’s position, he and Anne gave many balls. One evening as Anne, the hostess, entered the dinning room to greet her guests, she was started to see the man who had been the object of her love but a few years before and was supposed to be dead. One can only imagine the feelings of these two people as this first greeting for as it had been said, love does not die in death, but only in separation and hatred. As fate would have it only in fiction, Richmond Thackeray died three years later and Anne married her lieutenant, now Major Carmichael-Smith.

Early Life

When Thackeray was just five years old he was sent with another little cousin back to England. Many believed that the climate in India was bad for young children, so they were all sent back to England to live with relatives or in boarding schools. The parting with his mother at this time was almost more than his little soul could bear. He had been the focus of her total affections since his birth, and he idolized his mother.

In England he was greeted by kind relatives with whom he stayed a short time. One day his aunt, placed her husband’s hat on young Thackeray’s head, and found that it fit. Concerned that he might have water on the brain, she took him to the local physician, who told her not to worry. He had a large head the doctor said, and plenty in it. After his short stay with his relatives, he then was sent to a private boys’ school which was highly recommended to the parents in India. Thackeray wrote of this experience:

We Indian children were consigned to a school of which our deluded parents have heard a favorable report, but which was governed by a horrible little tyrant, who made our young lives so miserable that I remember kneeling by my little bed of a night, and saying, “Pray God, I may dream of my mother!”

Although Thackeray was generally like by his peers, one day two older boys forced him into a fight. During the fight Thackeray’s nose was broken and permanently flattened.

Thackeray was not motivated in school and showed no promise except drawing. He continually drew his teachers and fellow students in caricature. In the evenings he drew scenes from his lessons.

When Thackeray was nine, his mother and husband returned to England. The exchange between mother and son at this greeting must have touched Thackeray deeply, for he later wrote: “A veil should be thrown over those sacred emotions of love and grief. The maternal passion is a sacred mystery to me.”

When Thackeray was near the age of eleven, he was sent to public school. English schools at that time were in urgent need of reform and later received some sharp attacks form Thackeray’s pen. The poor quality of education was a frequent them in Thackeray’s journalism. The school Thackeray attended was called Charterhouse. The experience there was so bad that later when he wrote a satirical article on education, he renamed the school, calling it “Slaughterhouse.” In the article he wrote of the evils unsupervised boys were exposed to, for the boys at Charterhouse were boarded near the prostitute-haunted streets round about. “Boys used to go … out of their way to see the wretches hanging at Newgate [prison];… books of the vilest character were circulated in the long-room… Both morality and religion were ignored.”

Thackeray was concerned about the deep and lasting effect on young boys of the exposure to brutality and prostitution. He was later to write of the university:

I should like to know how many scoundrels our universities have turned out; and how much ruin has been caused by that accursed system which is called in England “the education of a gentleman.” Go, my son for ten years to a public school, that “world in a miniature”; learn “to fight for yourself” against the time when your real struggles shall begin… You have learned to forget (as how should you remember, being separated from then for three-fourths of your time?) the ties and natural affections of home… My friend … had gone through this process of education and had been irretrievably ruined by it.

Thackeray never sent his two daughters to public school.

Throughout his entire educational experience, Thackeray was never a motivated student. However, at Cambridge he did read and enjoy the classics, and he loved Greek plays. After a couple of years at Cambridge, he came of age and received his inheritance. He spent it most unwisely. So-called friends introduced him to gambling, and he spent much of his time an resources in its pursuit. Gambling became a parasite to his nature which took him years of struggle to overcome.

Working and Marriage

Thackeray left the university and moved to Paris in order to become an artist. He traveled to Wiemar where he met with the aging Goethe and reveled in the influence left by the great Schiller. When he returned to Paris, he discovered that the investment house in which his father’s money was invested had failed. Because of the failure, Thackeray was forced to live for the next several years on what he could make. He had to rely on his own talents, something he probably would not have done without this seeming tragedy. He began to write short illustrated essays for magazines, but he received only a pittance for his work.

In Paris he met and fell in love with seventeen-year-old Isabelle Shaw, the daughter of an Irish man and woman. Her father had served in the army in India and died there, and Isabella lived with her overbearing mother, who opposed the young couple from the start. At last, however, she relented and signed the consent form that was required because her daughter was under age.

Theirs was a happy marriage. They had three daughters in three years. The responsibility of a family made Thackeray become very serious about his work. His marriage gave him stability and greater meaning in life.

Soon, however, tragedy struck when their second baby died at eight months. Isabella was especially affected. After the third baby was born, Isabella had several fevers and did not recover from the depression that accompanied the birth. Deeply concerned, Thackeray took her on a series of trips. Each trip seemed to bring a little temporary relief, but nothing cured it. Little was understood about mental illness in Thackeray’s day so when she became so ill that she could not take care of herself, Thackeray arranged for her to live in a home with a couple.

Losing his wife in this way was Thackeray’s greatest sorrow of life. He never fully adjusted to his loss. An elderly Irishman once accused him of writing a book which made fun of the Irish. “God help me!” said Thackeray, turning his head away as his eyes filled with tears, “all that I have loved best in the world is Irish…. I was a happy as the day is long with her.” As trying as this experience was for Thackeray, he did not allow it to sour his life nor did he sink in despair. Rather, the experience mellowed him, filling him with courage and a great tenderness for all human sorrow and suffering.

Novels

Thackeray’s greatest work was ‘’Vanity Fair’’, which rose to great popularity. After its publication he was invited into the highest social circles.

Although he now made good money, he felt he needed to provide for his daughters after his death. These feelings made him sensitive to others who might also be in need and he spent much of the money he did have helping those in need. He began giving a series of lectures in an effort to increase his income. Twice he came to the United States and was well received as a lecturer. He was sympathetic to the history of his country. When asked what he thought of Washington he said: “I think the cause for which Washington fought entirely just and right, and the champion the very noblest, purest, bravest, best of God’s men.”

Near the end of his life Thackeray’s health was not good and some of his later work began to show signs of his illness. On Christmas Eve, 1863, having worked until evening, he returned to his home to rest. Later that evening he died.

Thackeray’s good friend Mr. Synge described how Thackeray, sensing his death, gave him a book to comfort him when he died. Synge said,

I took from its shelf the book he pointed out; out of it fell a piece of paper on which Thackeray had written a prayer, all of which I do not pretend to remember…. He prayed that he might never write a word inconsistent with the love of God or the love of man: that he might always speak the truth with his pen, and that he might never be actuated by a love of freed…. The prayer wound up with the words “for the sake of Jesus Christ our Lord.”

Copyright © Taken from the book, The Other Eminent Men of Wilford Woodruff. Special thanks to Vicki Jo Anderson. Please do not copy. 1

Associated Locations:

- Calcutta, India – Birthplace

Associated Dates:

- 18 July 1811 – Born

2 Responses

hello,nice article.do you know any books on thackeray’s life.i,m looking for paperback biography sources.thanks.

DJ Taylor’s biography is the most thorough!